In the world of fiction, writers tend to divide themselves into two camps.

The plotters—J.K. Rowling, Michael Crichton, R.L. Stein—outline their books before they write them. They know exactly what’s going to happen before they put proverbial pen to paper. They, in other words, plot.

The pansters—Margaret Atwood, Stephen King—as the name suggests, fly by the seat of their pants. They start with a scene, an idea, a question, a character, and they write.

Lately, another term has appeared on the scene: Plantser. A mash-up between the two. Someone who does some plotting and also spends some time flying by the seat of their pants.

I’m that middle person.

And this is how I wrote and edited my first novel.

* * * * *

My novel started with two things.

The first, a fear: What if you accidentally ruined someone’s life?

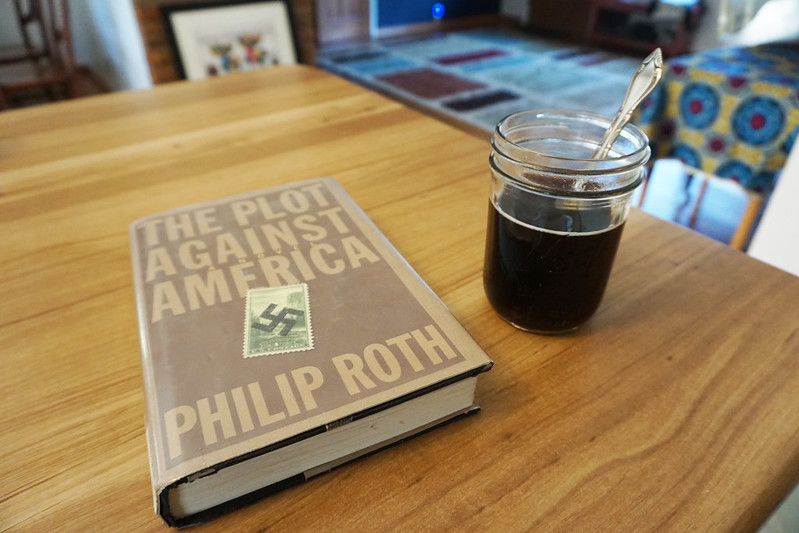

The second, a setting where one small shift in history has created a world very different from our own: What if the Nazis had won WWII?

From there, the plot started to take shape.

I knew the scene that started everything (the accidental ruining of a life) and I knew the world that would frame every choice the characters had to make.

So, I wrote those first scenes. I ran chapters one and two past a writing group. Only then did I pause and plan, asking myself where I wanted this character to end up, what would be the tipping point in his life?

Once I knew where I wanted to take him, I had to answer the question of how. How would he and certain other characters meet? How would X event that needed to happen come about? What was the logical, believable, true-to-who-he-is way for events to unfold?

Before I wrote on, I plotted.

I answered those questions. I talked the answers out with my partner and one of my best friends.

But I didn’t plot the whole book.

Just how to get the characters from what we call the inciting incident (the thing that changes the character’s world and propels them willingly or unwillingly toward a critical life choice) to the critical choice said character must make. The life or death decision. The choice that forces him to weigh his safety against his soul.

I still didn’t know how I was going to get the character past that critical life choice and to the ending I had in mind, but once I had those first answers, I didn’t worry about the rest yet. I wrote.

I wrote about a third of the book. I wrote until I ran into a snag: a plot point that wasn’t quite as believable as I’d hoped, that didn’t quite work. My main character wasn’t a hero and I’d planned on having him act like one. It simply didn’t work.

So, I stopped again. I thought. I planned. I ran ideas past my partner. And once I’d worked through it – plotting how to get my main character past that critical point and to the next critical turn in the story – I started writing again.

This is how the rest of the book unfolded for me.

I’d write until I hit a snag or a point in the book where I no longer knew what was going to happen. Then I’d pause and think, take long walks and talk to my characters, sit and jot down notes about how that character felt or saw the world, research more on Hitler and the Nazis, until something took shape. Then I’d write again. Until the whole thing was there – the whole story, the whole plot.

A complete first draft. An entire story arc.

At which point, of course, it was time to celebrate.

And then to edit.

The First Rounds of Editing

My first edits were simple ones. Different characters and scenes had come to me differently, which meant the book had several different tenses in it. I had to clean that up, pick a tense and stick with it – or at least logically separate tense by section.

I also cleaned up some typos and the occasional awkward phrase. I fixed a couple small points where I’d accidentally changed a minor character’s name partway through or miswritten one of those complicated Nazi ranks (military ranks are the kind of thing that don’t stick with me at all). I went back to a few spots I’d marked for further research because I wasn’t sure what kind of toys would be available in the 70s in Germany or because I hadn’t named minor characters yet.

And when I felt that I’d spent all my creativity and needed outside opinions in order to move on, I did a first chapter test…

The First Chapter Test

While I was working on edits, I stumbled across an article about testing your book’s salability. In the article, the book coach suggests testing your book title, first chapter, and synopsis on real readers (not friends and family) along with a series of specific questions.

What an incredibly brilliant way to figure out if your book is something someone would pick up off the shelf, read, and buy.

I decided to give it a go. But I also wasn’t ready to reveal the whole story, so I skipped the synopsis and put in my book blurb instead.

First, I chose six readers. I started with five, but one of the people who volunteered wasn’t really my ideal audience, so I pulled in a sixth in case he was an outlier in his feedback (which he did end up being).

I found those readers via Facebook and I mostly chose people I barely knew; only two of those readers were people I’d met in person and both of those fall into the category of acquaintances. I didn’t want family or friends who might try to sugar coat things, but I didn’t mind having people who already liked and followed my work.

I also tried my best to pick people who were not themselves novelists. I didn’t want a writing critique in this case. I wanted to know if someone who loves books would pick mine up off a bookstore shelf and end up buying it. For me, this was one of the huge revelations of this process. Critiques from writers and critiques from readers are extremely different things and both are useful in different ways.

As per the blog post, I included the title + two questions, the first chapter + two questions, and the back cover copy + two questions.

Then, to test a secondary back cover blurb, I picked five more readers (about 15 – 20 had responded positively to my original Facebook post, so I just went back and asked the next five on the list if they’d like to read). They got the same package as the first, except with the other back cover blurb option.

Now, the results:

:: Of 11 readers, 10 actually read and responded.

:: Two (including my outlier who is not my target audience) were not sure they’d keep reading after the first chapter. Eight definitely would.

:: Interestingly, male readers were okay with the title. Female readers hated it. No one really loved it. (Which, of course, had me working on alternate titles.)

:: With some variation in language and exactness, everyone was absolutely spot-on with what they thought the book would be about after reading the first chapter.

Obviously, they didn’t know the finer points. But when asked what they expected next, they all answered along the same lines and, to my delight, the questions they expected answered were the same things the next four chapters were about to address.

:: The reasons the eight wanted to read on were the same points of tension/questions I was trying to introduce, so I felt like the first chapter had done the job I set out for it. (This was key and was the main thing I wanted to assess with this exercise.)

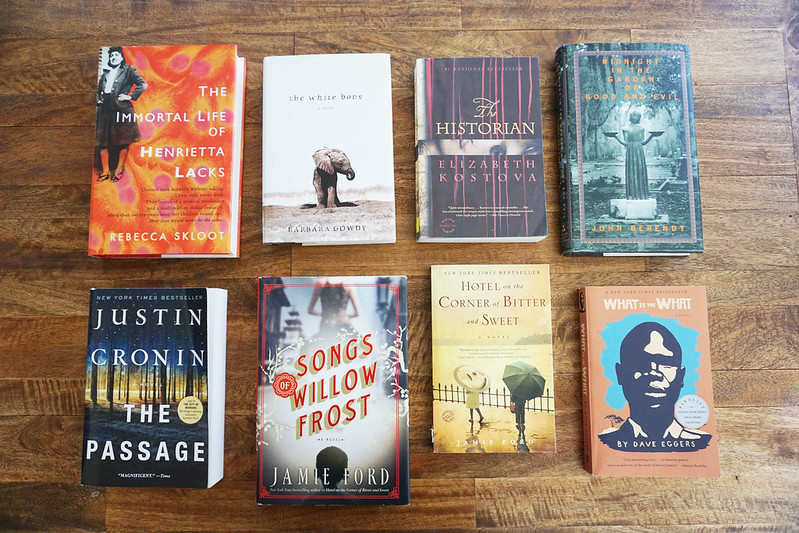

:: To my surprise (and joy), several readers compared the first chapter and premise to some of my comp titles*. So that made me feel like I was on the right track with those. (I didn’t ask what books they’d compare it to, so was surprised and happy to see several of them made comparisons when talking about their expectations.)

* A comp title, if you’re unfamiliar, is a published book you compare your book to – kind of like Amazon’s “if you liked X, you’ll also like Y” algorithm.

:: Of the two people who wouldn’t read on, both had the same issue, which was very small and easy to fix. So that also felt like a win.

In summary: I’m really glad I did this exercise. I found one small sticking point in the first chapter to fix, discovered that I need a much better title, and also ended the exercise feeling more confident that I’d actually done what I’d set out to do with that first chapter, that my book was sellable and marketable, and that it resonated with my current readership (which was not a given since my past work has all been non-fiction).

Critique Partners & Editors

While I was getting those first chapter readers, I was also soliciting my first few multi-chapter readers. I traded the first 30 pages of my manuscript with two other writers, asked another writer whose book I’d read and given feedback on about a year ago if he’d return the favor, and hired an editor to give feedback on the first 50 pages.

And then I hit a snag.

The feedback from this handful of people was all over the place.

A scene one person thought was unnecessary was another person’s favorite part. Something that spoke to one person another skimmed past.

There were only one or two points of agreement and those were easy to fix…but the rest was a mix-mash of advice that mostly contradicted itself.

It was the opposite of my first-chapter read experience.

Instead of clarity, I got utter confusion.

Which left me frustrated and despairing.

How was I supposed to edit this when there was so little overlap? Which person’s opinion was right?

This is when I asked an agent for her advice. And she told me two things that helped: 1) it was time to get full manuscript reads – not just the first 50 pages, and 2) I needed to make sure I was asking the right questions. Just crossing my fingers and asking for general feedback wasn’t working.

Also, I needed to make sure I had the right readers. If I’m aiming for thriller, a literary fiction lover might not be the right person to ask for feedback.

So I set off to do just that…

The Real Beta Read

I fixed up the couple small consistent things my first critiquers pointed out and then set off to find myself some full-length betas. This time, I decided I wanted avid readers who were not also writers. I didn’t want feedback on the craft (yet). I wanted feedback on the story.

I wanted to know, if they picked the book up at the library or the bookstore, would they keep reading? I wanted to know how they felt about the characters. I wanted to know what they thought would happen next – was I giving too much away? Not enough? I wanted to know if anything in the book was confusing or implausible.

So, first I reached out to a few friends who love a good story and who, to the best of my knowledge, don’t write fiction themselves. A couple were writers, but writers of ad copy or snarky financial articles or something else not related to fiction. Four of those avid readers said yes, they’d give my book a read.

Then I posed a question on Facebook: which of my followers were part of a book club and would be willing to answer a question or two for me?

I got three responses and privately messaged all three. I told them I was thinking of asking a book club to beta read my novel. I thought being a fly on the wall as a group of smart avid readers discussed the book would give me ideas and direction. I asked if they thought it would sound fun and compelling for book clubbers to have the opportunity to read something pre-publication and to have a possible hand in shaping it in the end.

All three said yes, that would be interesting. And all three offered to ask their book clubs if they’d be interested. One planned its books much too far in advance, so I declined the offer. The other two offered to see if their book clubs would switch to my book for their June meetings. I sent them the back of the book blurb and the first chapter to help them decide.

Both clubs gave a resounding yes!

I scheduled time to Skype into both meetings at the end of June.

Finally, I went in search of three to four more readers. I wanted a grand total of 10 (counting each book club as one). And I wanted to make sure I had the right readers.

So I put out a call here on the blog. I asked for people who were avid readers (reading at least a couple dozen books a year), who could commit to giving me feedback by July 1st, and who were willing to be honest, but still kind. I told them they were under no obligation to plow through the book if it didn’t capture their attention, but that if they did stop reading/decide to give up on the book, they had to tell me where and why.

I sent those who were interested to a short form where I asked them for a short list of some of their favorite books, genres they typically read, a sentence or two on why they wanted to beta read for me, and info on how they’d like to read the book (PDF? On their Kindle? On a Nook?).

I used those first couple questions to figure out which were my ideal readers. Were any of their favorite books something I aspired to? Were they in genres that had a similar pacing to my book? Did they want to read my book because they were long-time fans of my non-fiction work? I factored all this in and chose four more betas from the 15 or so responses.

I also was delighted to learn that another book club had offered to beta (through that blog post) and I told them I’d love to have them weigh in.

Then I took their answers to that last question (how would you like to read) and sent them the appropriate files (PDF, Kindle, or Nook).

Now, a short note on that: why format for Kindle and Nook when I could just send a PDF or Word file? Because I wanted to make it as easy as possible for people to beta read for me. I wanted them to feel like they were reading a real book – in whatever format they read books in. They could print it out. They could cozy up with their Kindle. I didn’t want formatting to hold them back from reading in bed or in the bath or in the car or wherever it is they typically read.

In whatever format I delivered the book, there were four or five sections scattered after important scenes throughout and they asked 4 – 5 questions each. Which character(s) did the readers feel connected to? Was there anything confusing in that section? Would they keep reading? What did they think was going to happen next?

The first beta read the book in two days. She said she was hooked and called it “binge reading.” She gave great specific feedback on what she wanted to see more of and, being a mother, helped me improve one of the young characters in the book.

That first feedback was an incredible boost. This was going to work!

The second and third feedback came in bits and pieces. One reader wrote to tell me she was 400 Kindle pages in (maybe halfway through?) and loving it. Another wrote to say she was excited for the book club discussion and to give me a short list of typos she’d noticed, which was very helpful.

Then on the same weekend, the second full-length feedback came in. She loved it. She had solid suggestions. And I was elated.

Then one of the first readers wrote to tell me that she and her brother (another of the first readers) went for a bike ride that morning and ended up discussing the book at length.

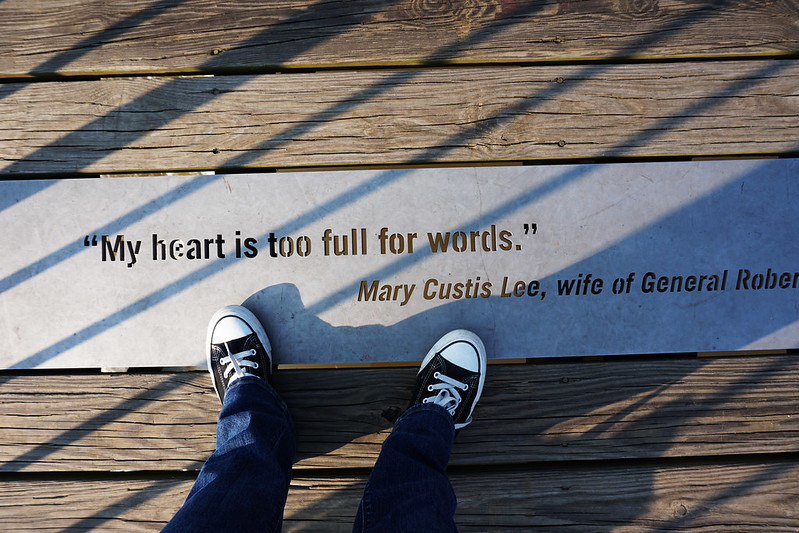

And, you guys, this is what it’s about. When you write a book, your heart is quietly hoping that this is the kind of book you’ve written. A story that people keep thinking about after they put the book down. A book they want to talk about. A book that grabs you and won’t let go.

These were just a few readers and beta reading is still an early signpost on the road to publishing, but the feedback rolling in was full of hope and excellent suggestions. Of all the milestones in my book journey, this was the place where I felt most excited to move forward and get this book into more people’s hands.

And so as the rest of the feedback came in, I parsed and contemplated and sent out effusive thank you notes…and then I dove headfirst and excitedly into edits.

Post-Beta Edits

I can’t tell you how many times during my edits I nearly cried with gratitude. My beta readers had really come through for me. I knew where the book needed to expand. I knew where things felt confusing. I had gone from having no more ideas to having dozens.

And so the book expanded.

And expanded again.

And landed around 65,000 words (about 20,000 more than where that first draft ended).

Sensitivity Reads

At this point, I felt like I was getting close. But I wanted some more input, especially on the new sections. And I wanted to make sure that my characters felt true to life and that I’d accurately represented the characters whose backgrounds are different than my own.

Which is where sensitivity readers come in.

If you aren’t familiar with the concept, it’s this: if you’ve written characters who come from a background different than your own (if you’re white and your character is Latinx, or if you’re writing a character with PTSD but you don’t have PTSD), you can hire someone from that background to read your book and look for issues in your portrayal. They can comment on it based on their own lived experience.

For example: someone who hasn’t suffered from depression might not realize that a huge feature of being depressed is feeling like you’re a burden on everyone around you and they’d be better off without you. Now, perhaps not every depressed person feels that way and certainly not everyone feels that way all the time, but it’s common. And you can find that out during research, but you can also check the accuracy of your portrayal by asking someone with depression to read your book.

Since I had several characters with backgrounds outside my own experience, at this point I found a couple sensitivity readers (one I already had beta-ing for me, but I asked her to read some of the new scenes). I also reached out to two psychologists well known for their work on things like PTSD and Stockholm Syndrome with some character-specific questions.

Both the sensitivity readers and the psych experts were incredibly gracious and generous with their time and help.

I took their feedback and massaged the book a bit more. And then I went through another few rounds of smaller edits. I searched for common words and diversified my language. I went through chapter by chapter and made sure there was at least one descriptor that wasn’t visual (adding smells, tastes, etc.). I went through and read each character’s perspective separately, tweaking where I found that one person’s voice had bled into another character’s part of the story.

And finally, when I found that all I was doing anymore was moving commas around and tweaking sentences, I decided the draft was done.

Or, rather, not done, but done enough to start querying agents.

Querying

If you aren’t familiar with the publishing world, here’s a quick primer:

If you want to be traditionally published (rather than self-published), you generally need a literary agent. And to get a literary agent, you need to query.

Querying is the simple (and oh-so-hard) process of emailing agents to propose your book idea. In order to do this, you’ll need a query letter, which includes:

:: A short, compelling description of your book (like what you’d find on a book’s back cover) that makes the agent want to read more

:: A line about why you think that particular agent might be interested in your book (did they sell a similar book? Do they love books about talking dogs and you wrote an awesome book about a talking dog?)

:: A paragraph about your writing credentials/background

:: Genre for your book (authors are apparently bad at figuring this out, so ask for help and don’t be too stressed if you’re just guessing)

:: Word count for your book (agents may not want to see something that’s got an extremely high or extremely low word count, so it’s worth looking up industry standards for your genre)

:: Comp titles (comparable books already published – this is optional)

:: Anything else relevant to whether they might want to see your book (is it #ownvoices? Is there something special that makes you the person to write that book?)

Now, the above is a major simplification. Put simply: query letters are hard. Getting all that info into a one-page letter is a craft all its own. This is something I worked on while my beta readers were reading the manuscript, so by the time I was through edits, I felt like I had a solid one. But it took months. So I recommend starting early on your query.

(And if you’re looking for querying resources, start with Query Shark, Janet Reid’s blog, and Writer’s Digest’s series on successful queries.)

But back to the point: to get a literary agent, you need a query letter. And a completed manuscript.

By this point, I had both. So I started querying.

Where I Am Today

So, now, here we are.

If this book is going to be published, I’m still early in the journey. There will be querying. Then probably edits with/for an agent. Then probably edits with/for an editor. And possibly more than one round of edits in each of those cases.

The road to traditional publication is a long one.

In fact, even the querying road is usually a long one. Occasionally, someone’s book gets snapped up by an agent right away. But when I asked a group of published authors how long it took for them to land their agent and how many queries they sent out, the average answer was over 50 queries (with the highest person topping out around 150, I think) and many months (with the longest person noting that it took her eight years, but that her book eventually found a home).

And so, for those who have been wondering what happened with the book project, this is the answer. After many rounds of edits and beta reads, sensitivity reads and more edits, I’ve started querying agents. And now begins the waiting game (and the hard part).

And while I’m waiting?

I’ve started a new project.

Because I desperately loved writing that first book. And I’d like to write another.

This one is straight historical fiction. A real-life revenge story a la Count of Monte Cristo but with two badass female leads.

Stay tuned.

2 comments

You could always publish the book yourself. It gives you a bit more freedom and a bit more stress aka heartache. It might be worth it.

Certainly always a possibility. But I’d like to go the traditional route on this one. Self-pub is pricier and more time consuming and I’m not as well versed in marketing fiction as I am with non-fiction.